This post will outline five of the research proposal mistakes I see most often and how you can avoid them while drafting.

The context provides the background information your reader needs in order to understand the problem. Let’s imagine your study is on the efficacy of lowering the legal drinking age. Before your reader can understand your study, they need some basic information, such as the current drinking age, the legislative history of underaged drinking, and the effects of alcohol on young people’s health. This information sets the stage for your study.

The problem statement outlines the specific problem you hope to solve with your study. For example, in our hypothetical drinking age study, we might be trying to solve the problem of underaged college binge drinking at parties. To establish that this really is a problem, we need present readers with information like the number of hospitalizations, arrests, expulsions, and so on, of drunk underaged college students. As you can see, this information is much more specific to the problem than the information about the general context.

How can you get this right when writing? The key is to outline. Brainstorm the problem and create outline sections based on the elements of the problem you identify. Then, zoom out—what do you need to know to understand those elements? Brainstorm again—these ideas become the sections of your context outline.

You also want to make sure you are using keywords relevant to your research questions. Identify keywords, then spend some time brainstorming their possible variations. For example, as well as “drinking,” you might want to search “drink,” “alcohol,” “alcoholism,” “binge drinking,” and so on.

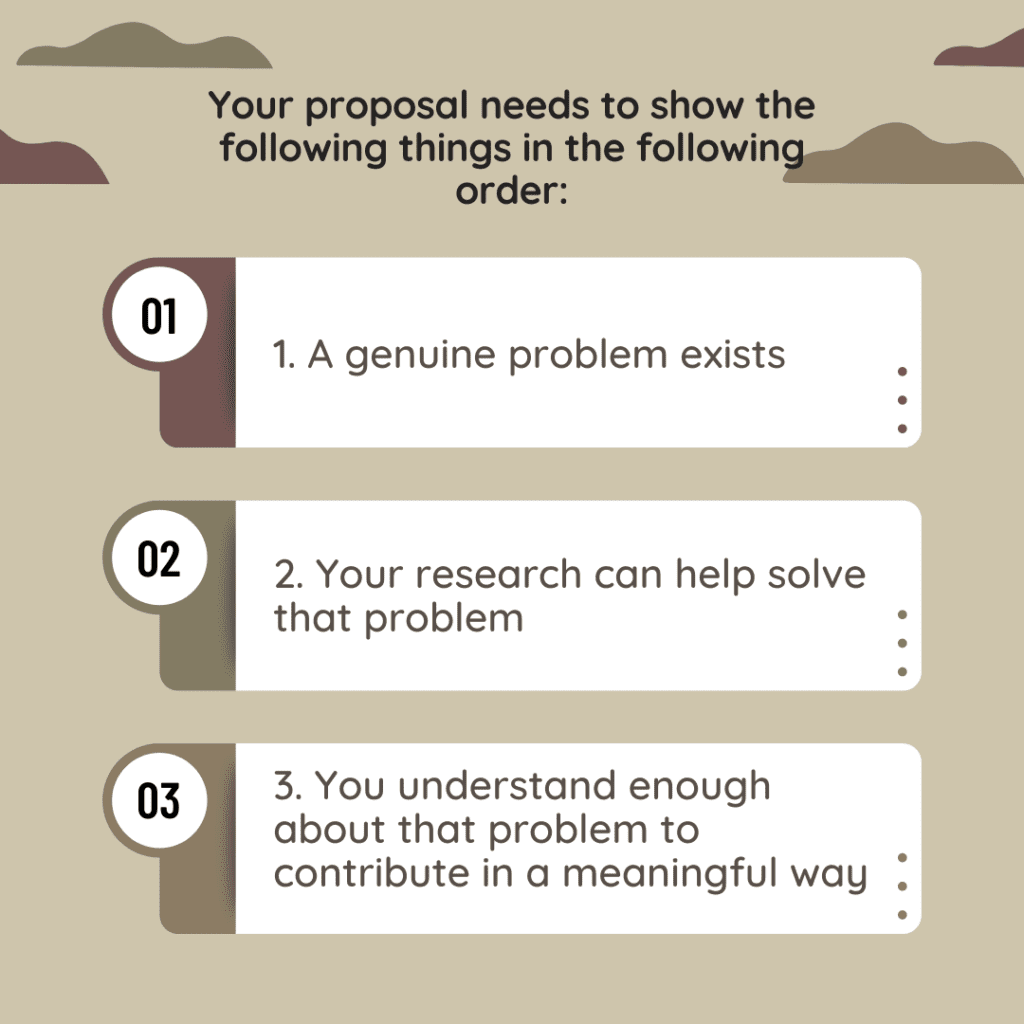

To achieve this, you need everything you present to line up clearly with your research questions. The context should be the context of those questions, the problem statement should show why they are relevant questions, the literature review should establish they have not been adequately answered already, and so on.

The solution when you are drafting is to use a chart. Put your research questions in the first column, your objectives (if applicable) in the next column, different aspects of the problem in the next column, key lit review sources and gaps you have identified in the next, and so on. Then check—does each row make sense and line up properly?

Research study design is complex—there are many, MANY possible variations within the four main design types (qualitative, quantitative, mixed-methods, and textual analysis). Many students find they “click” with one particular design style—usually the one they encounter most often, and thus understand best. Unfortunately, that style may not be appropriate to what your study is trying to achieve.

I recommend that students think about two key things when choosing a design style:

It is no good deciding to conduct interviews (qualitative study) if what you need is hard data for statistical analysis. Likewise, it is not a good idea to plan a study involving complex controlled-environment experiments if you have no access to a lab. Thus, you need to make sure your study design takes account of both your questions and your capabilities.

What if it doesn’t? Might be time to rethink your questions. (This is much less stressful to do BEFORE you submit your proposal.)

Remember your goal: you are attempting to demonstrate that your research will fit into a genuine research gap: that no one else has adequately answered the questions or solved the problems you are trying to solve. Show the work that has gone before, the work that remains to be done, and where you fit in terms of that final category.

Try structing each section of the literature review with those three questions in mind. For each RQ, begin by showing the work that has already been done. Then explain what those existing studies fail to do. Finally, end with a note reminding the reader that your study will try to fill that gap. Then, move on to the next RQ.

Achieve those three things, and you may find yourself in the happy position of being asked only to complete stylistic revisions!

Need help getting your dissertation proposal back on track? Find out how dissertation coaching can help.