This month, I am quietly introducing a new add-on service to my offerings, to support students who stop needing full-on coaching while they are trying to secure IRB approval. Thinking about what this service should look like and why is needed has made me realize just how many students really don’t understand IRB – what it is, why we have it, and why it is so annoyingly finicky to achieve.

Here are some interesting stories to get us started.

Each of these past examples highlights what can go wrong when ethics are not properly considered during research design. The IRB process in research is designed to catch issues with deception, harm to participants, unintended consequences, sloppy design, and so on. These real-life cases show us that this is not paranoia – even the most well-meaning and intelligent researchers can sometimes get the ethics wrong.

For most students, however, IRB feels like a huge, mysterious, and overwhelmingly difficult process. Many students get stuck at this stage for months, endlessly applying and reapplying, and unable to move on with their projects while they wait (because no data can be collected until IRB approval is received). Here’s how one of my recent students expressed it:

This is made even more frustrating by the fact that most students don’t expect IRB to be a long or difficult process. Unlike writing a lit review, for example, it looks easy on the surface – a short application form that can mostly be completed by copying and pasting.

Here’s why that assumption is wrong:

IRB are not looking for the same things your committee/advisors were.

Because they do not understand what is being asked of them and how to provide it, many students struggle more than they need to with IRB. It costs them a LOT of time and money, as well as impacting their mental health.

Simply put, IRB approval is an extra level of protection built in to the research approval process to ensure that human subjects and society are protected from negative consequences.

Well, the thing to remember is that you and your supervisors are very deeply concerned with (and hopefully excited about) the research itself – what you are trying to find out, the most effective way to find it out, and the benefits and value of finding it out. As example 2 above shows us, however, the most effective way isn’t always the most ethical way. Biases, influences, compensation, the manner of dissemination – all can have consequences that cut both ways. The IRB is there, therefore, to provide a more distanced set of eyes who are looking for one thing and one thing only – will anyone suffer because of your research?

For most students, the IRB process is long and painful because ethics issues are complex and can creep into just about any part of a study. The only way to ensure they are properly dealt with is through painstaking detail about what you will be doing.

For many students, IRB is denied repeatedly because they don’t know what the issues are that they are trying to avoid, and so they don’t include appropriate detail to address them.

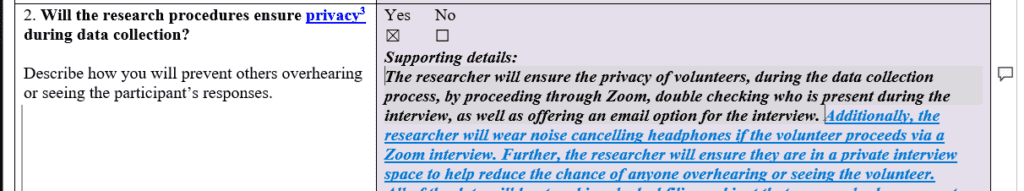

For example, one key concern of IRB is the protection of privacy (think about the unfortunate subjects in the second example above). When answering the question “how will you ensure the privacy of participants during data collection?”, many students emphasize collection within a private space.

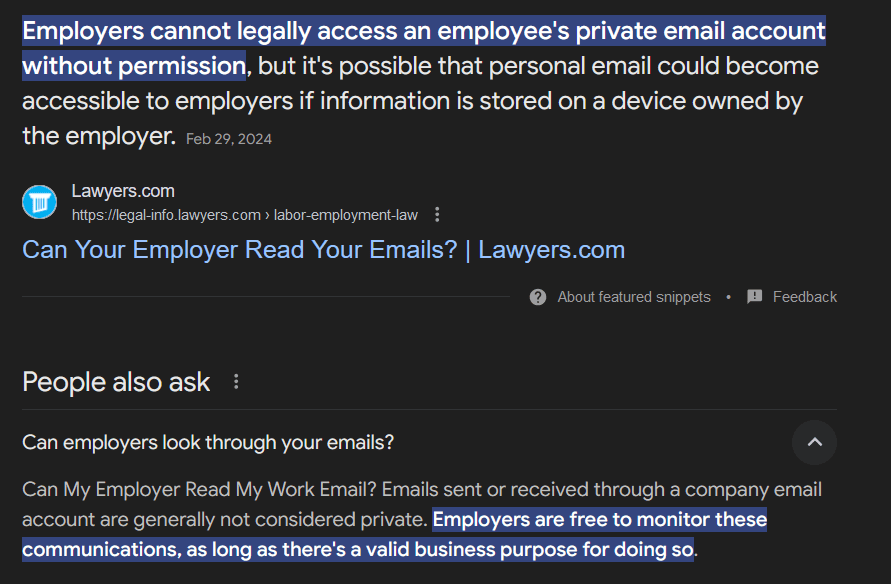

However, there is more to consider. How, for example, will you ensure that the participant is in a private space? What, exactly, does “private” mean in this day and age? If you are interviewing a participant who works in an institutional setting and the interview takes place on an institutional device, or if interview data are later shared through an institutional email account, that institution may have access to that data and the right to examine it. The participant might not be aware of this, but if the data concern that individual’s employment within the institution, their job may be placed at risk. It is your job – and not the participant’s – to anticipate this possibility and provide for it.

The IRB don’t want you putting out fires as you go – because you may accidentally make mistakes. They want you to be fully prepared with a plan to avoid, mitigate, or eliminate any ethical issues that comes up as you work. That’s why IRB takes so long. Each new detail you provide will spur more questions from the IRB, digging for even more detail about what you will do and how you will do it. The only way to avoid this is to fully anticipate all potential ethical risks before you start, and discuss them in full on your application.

Think of IRB a bit like you might think of a court case. Put your lawyer hat on. What may seem obvious (getting participants’ consent) or unavoidable (outside funding) to you will still need to be discussed in painstaking detail in your IRB application, to show that you have taken care of any potential loopholes.

If IRB is a court case, the quickest and easiest way to success is to have the help of a lawyer. You need someone familiar with the issues and the language appropriate for discussing them.

If you are approaching the IRB process soon, here is my advice to you:

Also, if you are stuck in what feels like an endless IRB cycle right now, reach out – I’m always here to help. (In fact, I have a new service just to help with this.) Book a free call and I’ll help you get started. 🙂